by Samuel Keast and Christopher Sonn, Edited by Susan Wolfe and reprinted from The Community Psychologist

Conceptualising values in research is one thing, negotiating them through the layers of relationships and constraints of a community organisation and a university is something else. This article highlights some challenges in navigating values of inclusion, voice, and collaboration through the implementation of a program evaluation. The program was developed specifically for youth from the African-Australian diaspora and was largely in response to the negative representations of these young people in the media and political discourse. The not-for-profit organisation has run a number of youth-focused programs, but this was the first of its kind to respond to the needs of young people from the African-Australian diaspora.

Values-based research seeks to show how programs give voice to the wisdom young people have cultivated “at the margins of institutional betrayal and economic/racial/sexuality oppression” (Fine, 2012, pp. 355). Informed by values, methods are derived that can capture how programs have sought to foster “the embodiments of and survival skills honed in precarity” of young people faced with structural violence (Fine, 2012, pp. 356). Methods that adequately explore the complex psychosocial and sociopolitical identities of young people placed at the edges of communities by discrimination and racialization (Futch & Fine, 2014).

This means there is an important multidirectional relationship between researchers, program facilitators, program participants, and program stakeholders (Dutta et al., 2016; Fine, 2012). And the products of this kind of research-based evaluation are not regarded as politically inactive objects that report decontextualized facts, but rather that they form part of the re-imagining of radical possibilities through organisational and systemic change.

This reflection embraces Evans’ (2014) notion of ‘community psychologist as critical friend’ and will use the attributes of a critical friendship as a way to frame the processes of the project. One of the challenges as outlined by Evans (2014) in becoming a critical friend is having the time, energy (and we would add resources) to build and maintain community partnerships “that affords us the opportunity to function as critical friend” (p. 362). With increasingly short contracts, short timeframes for deliverables, and under resourced organisations and institutions this can be a significant barrier to the development of trusting supportive relationships required for critical friendship and this was certainly something this project faced. In brief, the interconnected attributes and functions of a critical friend are: co-creation of critical space, value amplification, problematising beliefs and practices, seizing teachable moments, sharing critical frameworks, critical action research and connecting community practice to networks and social movements (see Evans, 2014). Essentially these are to ensure as critical researchers we become “skilled at partnering with community-based organizations for social change without being co-opted into discourse and practices that simply maintain unjust conditions, or worse, exacerbate them” (Evans, 2014, p. 365).

We outline some of the contextual details of the program and the organisational relationships before moving into the ways in which the evaluation was conceptualised and the theoretical ideas underpinning it. We will then discuss some of the ways in which we negotiated these ideas within the various constraints of the organisational requirements on both sides. Through detailing some of the processes, relationships and findings, we hope to share the imperfections and lessons learned from undertaking an evaluation in this context.

The program and partnership

The not-for profit foundation of a professional sports club facilitated a community consultation, part of a response to the racist misrepresentations of African-Australian diaspora youth. Stakeholders at this consultation included: University staff, community Leaders, African community business owners, parents and young people from African-diaspora communities. It was also attended by representatives from state and local government, police, and school representatives. The community consultation gave rise to the African Action plan and 12-week program was developed in response to that plan. In the program students aged 14-18 were paired with a football player and community mentor with the intention to increase student engagement and provide information about employment and training pathways and opportunities. It also aimed to build interpersonal and personal skills through the use of mentoring, workshops and a goal-setting agenda. The pilot of the program began in early 2019.

The university has an ongoing relationship with the foundation and the club. Various research projects have taken part between them and it continues to be an important relationship to both parties. Program evaluations have been a cornerstone of this relationship and provide the foundation with an important source of institutional support for their various programs, whilst also providing the university with funding and opportunities for students to undertake placements and research projects. This evaluation was a part of a doctoral industry placement agreement between the university and the foundation. The placement supports a PhD student to gain industry experience with a small stipend.

Collaborative design

A series of meetings between key program staff and researchers were held prior to the commencement of the program where conversations arose about the values that needed to be a part of the evaluation process. Values that would honour the community consultations, respect and promote the voices of young people from the African-Australian diaspora and address the requisite policy directions. As researchers our work and values are centred around the awareness of power inequities and how we might co-create contexts, moments, or places that foster social inclusion. We work with a sense of justice that seeks to question and challenge the ways in which people are marginalised, racialized and de-advantaged by socio-cultural/political contexts, institutions and organizations. We also see justice as centring the voices, experiences and expertise of those who are being marginalized. From the outset the researchers recognised that concepts and measures utilised for more traditional program evaluation may not be able to meet these values.

Collaborative meetings continued throughout the evaluation and were often more informal and occurred at moments before or after program sessions. During these researchers were able to: listen to program staff reflect on sessions, engage with staff about the ongoing development of concepts and ideas for the program, workshop problems or issues arising within or around the program, and to continue problematising beliefs and practices.

For researchers the processes of sharing critical frameworks can often involve undoing more mainstream, culture-free research approaches in order to pursue more social justice oriented ones. In this case, partly due to the organisation’s previous exposure to more mainstream evaluation methods, but also the need for certain types of evidence produced pressures to provide simplistic indicators of the program’s success.

One of the ways we aimed to share our critical frameworks was through providing literature that not only informed the evaluation process, but that could also be used to inform the ongoing development of the program. So careful consideration was given to the kind of literature used and its accessibility so as not to alienate the organisation from the process of problematising the way we understood the issue. The researchers chose five mains concepts to inform the work and the program: the youth engagement continuum (Pittman et al., 2007), sense of community (Pooley et al., 2002; Pretty et al., 2007; Sonn et al., 1999), sociopolitical development (Fernández et al., 2018; Hope & Jagers, 2014; Watts et al., 2003) and capacity to aspire (Appadurai, 2004). Central to all these were critical questions about how young people, particularly racialized young people, are often (mis)characterised and disempowered by traditional structures and institutions.

The status quo of many not-for profit organisations is well-intentioned service provision for populations ‘in-need’ or ‘hard-to-reach’, but these intentions flatten criticality which is “needed but rare” and “pragmatic thinking and technical solutions such as logic models, evidenced-based curricula, performance management frameworks, and the obsessive counting of participants served have displaced critique of the status quo and imagining future possibilities” (Evans, 2014, p. 357). The challenge for this project was not only to evaluate the outcomes of the program, but to build understanding about the realities for young racialized people in Australia, how they navigate unreceptive communities, whilst also building their capacity to aspire.

Researchers in this project sought to challenge how these young people are often conceived as being ‘in-need’, and to counter this build into the evaluation methods that would capture how these young people saw themselves in the world, their communities, and their futures. Although we used more traditional methods (observations, interviews, qualitative questionnaires) we also used mapping (Futch & Fine, 2014) as a method to engage with students. In weeks three and 12 of the program the students did their mapping sessions which sought to offer them a way to creatively express their identities, their lives and the social support around them and to be a conversation point with researchers. A wide range of materials for creating their maps was provided (e.g. paper, paint, canvases, glitter, glue, stickers, stamps and an array of drawing instruments).

An example of the mapping from the first session can be found in image 1. The student who produced this canvas made continual changes so that it evolved over the length of the session. At first, she painted the entire canvas black, they then squeezed glitter of varying colours over the black background. When asked how this represented how they saw themselves in the world they replied, “the world is black, but it depends on how you look at things” (and pointed to the glitter). Upon returning later in the session the student had covered the canvass in black again, obscuring the glitter. They told researchers now it was about social media and fame and how simple or ordinary things could become popular or unpopular, like the now black canvas. Returning again, the canvas had been readorned with shaped sequins and feathers. When asked about this new form, the student replied it was about “layers” and that you “shouldn’t judge a book by its cover”.

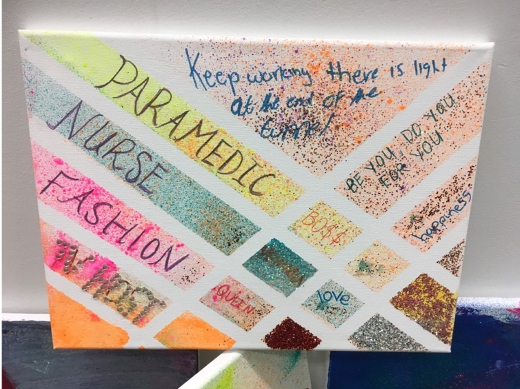

The second mapping session invited students again to depict how they saw themselves in the world, but also to reflect on how things might have changed having participated in the program. It was noted by the researchers that students on the whole were more collaborative during this session, often helping each other co-create maps. Image 2 shows a map from a female student from this session and like many others from this session they were celebratory, colourful and focused on positive messages about their identities, and/or their futures and vocations. These two examples are a snapshot of the overall collection of data for the evaluation but provide examples of how we attempted to use creative and appropriate methods, that elevated the voices and lives of the students from their perspectives in the evaluation.

Some of what we concluded for future programs

For the program to move beyond service delivery and toward systemic change future programs like these should engage more in the sociopolitical development of young people. This means, extending the content beyond generic youth development toward engaging young people in critical social analysis as future social change agents in their communities. In future planning prospective program participants should be consulted about how they’d like their community represented within programs.

While the researchers acknowledge the limits of resources available to such programs, our experience highlights how vital it is for programs to understand who participants and their communities are, and what those communities mean to them. To achieve a balance between flexibility and structure, programs need to have well-developed and evidenced models that can inform the best strategies for program delivery. Future focus also needs to acknowledge the reality of the contexts which racialize certain young people and that through sociopolitical development they can build capacities for civic engagement and social action.

What we concluded about our work – Were we able to be critical friends?

As researchers regularly engaged with concepts and literature it can be easy to forget that those working in program delivery often do not have the time to devote to learning new critical frameworks and that perhaps some of our earlier teachable moments contained too many concepts that were new to the organisation and program. Perhaps a more scaffolded approach could have made these teachable moments more successful. This could also apply to the ways in which we worked with problematising beliefs and practices, which although arose at specific times throughout the program, there was not a process or space established by which critical reflection could become a part of the work the organisation did. Some of the questions that linger from our reflections are: How do we leave problematising as a critical skill once we have left? And how do we introduce or foster a critical friendship between program staff and their own organisation?

Author Information

Samuel Keast, PhD Student, samuel.keast@live.vu.edu.au Victoria University, Institute for Health and Sport, Australia

Professor Christopher Sonn christopher.sonn@vu.edu.au Victoria University, Institute for Health and Sport, Australia

References

Appadurai, A. (2004). The Capacity to Aspire: Culture and the Terms of Recognition. In V. Rao & M. Walton (Eds.), Culture and Public Action (pp. 59–84). Stanford University Press.

Evans, S. D. (2014). The Community Psychologist as Critical Friend: Promoting Critical Community Praxis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, n/a-n/a. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2213

Fernández, J. S., Gaston, J. Y., Nguyen, M., Rovaris, J., Robinson, R. L., & Aguilar, D. N. (2018). Documenting sociopolitical development via participatory action research (PAR) with women of color student activists in the neoliberal university. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 6(2), 591–607. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v6i2.900

Futch, V. A., & Fine, M. (2014). Mapping as a Method: History and Theoretical Commitments. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2012.719070

Hope, E. C., & Jagers, R. J. (2014). The Role of Sociopolitical Attitudes and Civic Education in the Civic Engagement of Black Youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(3), 460–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12117

Pittman, K., Martin, S., & Williams, A. (2007). Core Principles for Engaging Young People in Community Change. Forum for Youth Investment, Impact Strategies, Inc.

Pooley, J. A., Pike, L. T., Drew, N. M., & Breen, L. (2002). Inferring Australian children’s sense of community: A critical exploration. Community, Work & Family, 5(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800020006802a

Pretty, G., Bishop, B., Fisher, A., & Sonn, C. (2007). Psychological sense of community and its relevance to well-being and everyday life in Australia. The Australian Community Psychologist, 19(2), 6–25.

Sonn, C., Bishop, B. J., & Drew, N. M. (1999). Sense of community: Issues and considerations from a cross-cultural perspective: Controversy and contentions. Community, Work & Family, 2(2), 205–218.

Watts, R. J., Williams, N. C., & Jagers, R. J. (2003). Sociopolitical Development. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31(1), 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023091024140